- VitalCore Newsletter

- Posts

- Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence

How to make your ideas noticeable and memorable

You have a brilliant idea to help your company. Something that could streamline a process, or launch a new product, or fix a costly problem at work. Yet when you present it, the audience is distracted, unconvinced, or uncertain about next steps. What if there were a proven structure that could transform your message into one people notice and feel motivated to act upon? In the dynamic environment of modern organizations, being able to communicate clearly and drive decision-making isn’t just a bonus; it’s essential for progress. Enter Monroe’s Motivated Sequence: a time-tested approach for structuring your communication so it not only lands, but lasts.

Alan H. Monroe

Monroe’s Motivated Sequence (MMS) is a classic framework from communication theorist Alan H. Monroe. Although it originated as a component of public speaking, the sequence migrated into advertising and sales because it solves a practical challenge: How do I navigate the audience from hearing my idea to supporting it? MMS presents a solution by proposing a structure in which the audience first pays attention, then recognizes the problem, understands a credible solution, imagines the consequences of adoption, and finally knows what decision is being requested.

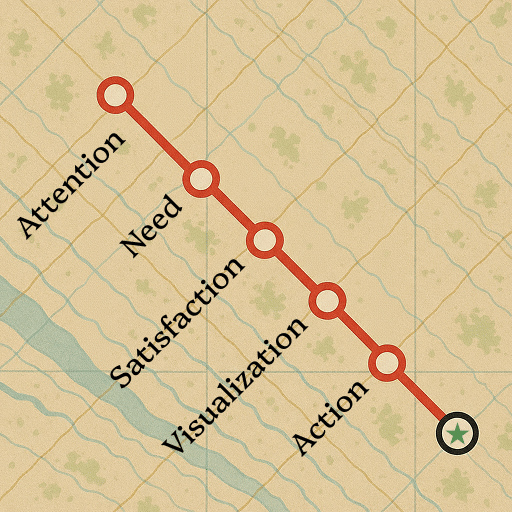

Attention

We start with capturing your audience's Attention by by making a connection, the more emotional the connection the better. In professional settings, for example, you may earn it by presenting something relatable and meaningful to the group - an operational bottleneck, a deadline, a missed opportunity, or financial implications. It's like the prick of a mosquito, a quick hook that captures the audience before they've realized what happened. Now that you've captured their attention, it's time to lead them into why your message matters.

Need

Why do we need to solve this problem? What happens if we do nothing? Create a connection with your audience by relating your message to something that impacts them directly. In this phase, focus on negatives and consequences for an even stronger connection. Avoid doomsday scenarios or "sky is falling" points though, as they will likely overwhelm the audience to the point of desensitization. You're just introducing the itch of the mosquito bite, the harmless but irritating itch that only your message can scratch. If done properly, your audience will be thirsting for relief.

Satisfaction

Time for the core of your message - the proposed remedy and how it directly addresses the root cause of the problem. In a business context, this often looks like proposing a pilot project, a test run, or a clearly defined process adjustment. What matters most here is showing not only what the solution is, but how it will be measured. Lay out concrete criteria so that everyone understands what success looks like and disagreements can be anchored in evidence rather than opinion.

Visualization

Here, you invite your audience to imagine what success would look like. This phase is about painting a vivid, concrete picture of the near future - the direct improvements they could expect to see: fewer handoffs, reduced support bottlenecks, cleaner dashboards, faster turnaround times. Use a short narrative or sharp comparison that clarifies how life gets better, allowing people to easily grasp the benefits. The key is a true-to-life glimpse of what’s possible, showing just enough contrast with the current state to make change attractive, but without relying on hype or fear-mongering.

Action

The final step, Action, isn’t about issuing an order—it’s about making the path forward unmistakable. Here, you spell out exactly what decision is being requested and what happens next if the answer is yes: who will take ownership, when work begins, the milestones for review, and the signals that will indicate success or prompt a course correction. This definitive summary removes the uncertainty that so often lingers after a meeting, ensuring that momentum isn’t lost to ambiguity or hesitation.

Why does Monroe’s Motivated Sequence hold up so well in business environments? The answer lies in how each phase maps directly to the fundamentals of psychology and group decision-making. When you start by capturing attention, you’re harnessing the principle of salience - people are wired to notice what feels urgent and relevant. The need phase grounds the message in a clearly defined problem; when teams can’t agree on what’s wrong or why it matters, conversations easily spiral or stall. Offering a concrete solution (satisfaction) addresses the human craving for control and testable remedies. Your audience needs to see not just a fix, but one that feels within reach. Asking them to visualize the outcome leverages how people reason with mental imagery: by painting a picture of the near future, you’re making the abstract feel tangible and enabling others to “see themselves” in the new reality. Finally, closing with a call to action clarifies process and ownership, cutting through uncertainty and helping people move from talk to traction. While this sequence won’t force consensus, it reliably strips out common sources of hesitation and ambiguity.

If you look across modern organizations, you’ll spot traces of this structure everywhere serious decisions are made: in a decision memo that lands with a clear recommendation, in a product pitch with a story arc, in executive briefings that move from issue to proposed next steps, in incident reviews that make lessons actionable. Compared to AIDA (common in advertising), Monroe’s approach carves out more room for stating the problem and showing how a solution will actually be measured—a recognition that in business, the people in the room are accountable for the downstream results. Whether you’re presenting to operations (highlighting process gaps), to product teams (friction and customer outcomes), or to finance (unit economics and risk), you’re still guiding everyone from initial relevance to actionable resolution.

Of course, every framework has its boundaries. Monroe’s Motivated Sequence really shines when there’s a concrete problem to solve and a real path forward. It’s not well-suited for brainstorming, purely exploratory workshops, or early-stage relationship building, where the goal is to open possibilities rather than land a decision. And like any tool, it can lose its power if overused—especially if the visualization phase turns into exaggeration rather than clarity. The best communicators adapt the weight of each phase to the context, letting evidence show where warranted and leaving space for debate without losing structure.

For anyone heading into a meeting where a real decision is on the table, Monroe’s model serves as a practical checklist:

Have you made people care,

Defined the problem,

Shown a doable fix,

Painted a compelling outcome,

Spelled out precisely what needs to happen next?

Used thoughtfully, this framework can lower the friction in group decision-making, helping teams move from scattered discussion to shared clarity and meaningful action.